Consciousness, the Skeleton Key

The way out of all messes

I recall once reading an article by David Chapman that said every position on consciousness is incoherent. Google (whose quality is seriously degrading) failed to find this article, and so did ChatGPT, but that did give me the following quote:

Every position on consciousness I know of is incoherent, including my own. And so is every proposed way to dispel the illusion of consciousness.

Did Chapman actually say that, or did ChatGPT hallucinate? Does it matter? Because facts are facts: we can’t say coherent things about consciousness. So let’s take a look at the junkyard that philosophical discussion on consciousness amounts to. Starting with the mainstream position: physicalism.

Physicalism

This one means that only the physical exists, and that therefore consciousness is something physical. It falls apart on the hard problem of consciousness, which is simply the observation that no matter how well you understand a brain, it won’t tell you why there is anything it is like to be that brain. This is so because when we observe the brain, we don’t observe consciousness, just neurotransmitters and electricity sloshing around. As Scott Alexander put it once:

When you see a tree (to be extremely pedantic) the tree doesn’t enter your head. What you’re seeing is photons that have bounced off the tree, hit your retina, gotten converted into electrical impulses, been shuffled between a few brain regions with names like “superior colliculus” and “thalamus”, gotten converted into different electrical impulses, and finally sent in a nice package to the little homunculus who lives in your neocortex.

Scientifically, there is no little homunculus, and yet, that is precisely how it feels like to be a being. The lack of this homunculus or of anything other than electrical impulses and neurotransmitters in the brain has led some to adopt what is easily the most extravagant notion philosophy has ever conceived in its wild history: eliminativism.

Eliminativism

Eliminativism is the notion that there is no consciousness. Eliminativists argue that we are mistaken as to the fact that we are conscious, and will often resort to showing optical illusions to demonstrate how our intuitions (such as the ‘intuition’ that we are conscious, if it can be called that) can be mistaken. But consciousness is no intuition: an optical illusion is a mistaken perception but it is still a perception. Their existence cannot be used to argue there are no perceptions. To be sure, eliminativists will also deploy quite wide ranging arguments in defense of their position, but there might be one very simple answer to all of it: Samuel Johnson is said to have refuted George Berkeley’s idealism (the notion all is mind, which we will get to later) by kicking a rock and saying ‘I refute it thus’. I would like to say we can remind eliminativists of their consciousness by kicking them. This should be fine, since after all, according to their own precepts, they are not conscious and therefore cannot feel pain. It would be like kicking a rock, an act with no moral valence. But we can do better.

G.E. Moore once claimed to prove the existence of an external world with the following argument:

Here is one hand,

And here is another.

There are at least two external objects in the world.

Therefore, an external world exists.

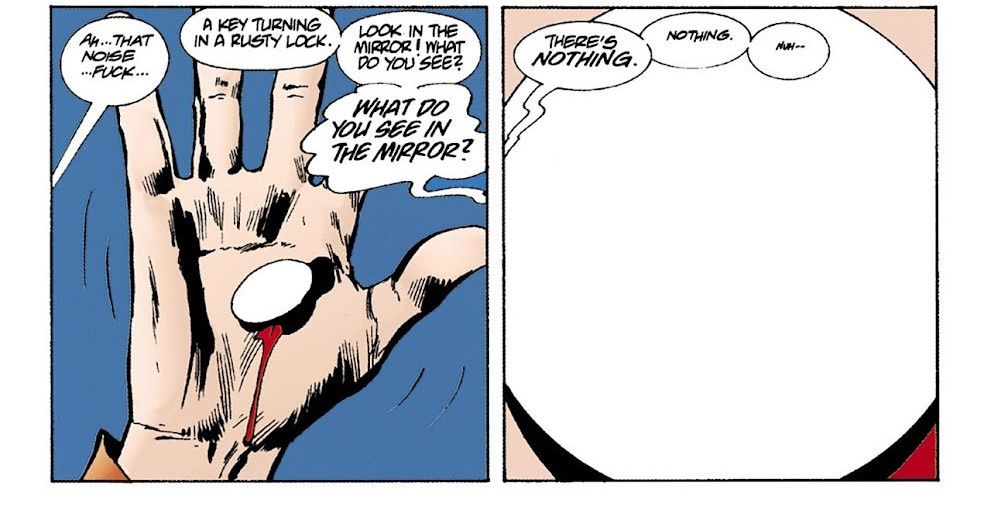

See, common sense can be quite a powerful thing. And when you are at the point you’re arguing there is no real difference between you and a rock, maybe take a look around? See one hand. See another. See a sunset. Then try to convince yourself it was all the same as being in deep sleep.

There is also a less extreme strain of eliminativism which simply asserts that concepts such as ‘beliefs’ or ‘desires’ don’t really exist. It falls down all the same to the previous counter, since if there is no desire, why do you do anything? Why are you not a monk? Sure, this eliminativist will say neuroscience will one day replace such ‘parochial’ concepts as ‘desire’, but you can’t argue against the existence of that qualia (qualia is a conscious percept or sense impression). The most neuroscience can do is complicate the concept, but to argue this complication means the concept is fake is missing the forest for the trees on steroids, it’s looking at a forest and saying there is no forest, just trees.

But eliminativism is just one extreme strain of physicalism. Another take on physicalism, one much more common, is reductionism.

Reductionism

This is the view that mental states reduce to neural states. The problem with this view is that to say you have a reductive account of X in terms of Y, you must be able to explain X solely in terms of Y. To see this clearly, let’s take a look at an experiment where scientists saw what people picture in their mind’s eye:

Electrocorticogram (ECoG) recordings were taken from 17 patients with epilepsy who had implanted subdural cortical electrodes related to visual perception. A decoder was trained to estimate the semantic meaning of the images that the patients were viewing from the intracranial ECoG recording using visual-semantic space. Based on the real-time inferred semantic information with the decoder, an image was displayed on a monitor placed in front of the patient. The patient then tried to display an image with instructed meaning by imagining it.

Superficially, this seems like they have successfully reduced consciousness away, but here’s the catch: imagine an experiment where you get the signal sent to a monitor, and you try to reconstruct the image displayed in it from that signal. You can surely succeed, but should you doubt your success, you can always check your reconstructed image against what you see by just looking at the monitor. The researchers in this experiment did not have that option, because when you scan the brain, all you get are the signals: there is no little monitor in the brain you can look at to literally see what the mind’s eye sees. So the experiment proceeds by the patient trying to sync up what they see on the monitor with what they see in their mind’s eye, and that’s the only way it can work, because no one else can see what their mind’s eye sees.

To return to the analogy, you can see the signal that generates the image in the monitor, but you can never look at the monitor directly. You can create a duplicate image, but you can’t see the original.

This inability to see the original is why the reduction fails. You don’t have a reductive account if you can’t explain why these signals should generate an image in the mind’s eye (or why there is a mind’s eye to begin with), and that reductive account will never exist, because science explains the observable, and we are talking of something unobservable.

This may sound shocking, but we have been forced into accepting all manner of shocking things. Apocryphally, the Pythagoreans killed someone for insisting pi was real, and there really is something bizarre that a number that cannot be expressed as a fraction or ratio, a number that never ends, is inextricably bound up in the nature of reality. There is something bizarre in the impenetrable randomness of quantum mechanics, in positing (in a failed bid to salvage determinism) that a spread of probability is physical and that therefore there is an infinite number of unobservable universes. What’s one more impenetrable mystery to the pile?

Supervenience

Supervenience is the view that mind is a modification of matter. It is distinct from reductionism because it doesn’t posit that mind can be explained away. A good summation is:

A dot-matrix picture has global properties — it is symmetrical, it is cluttered, and whatnot — and yet all there is to the picture is dots and non-dots at each point of the matrix. The global properties are nothing but patterns in the dots. They supervene: no two pictures could differ in their global properties without differing, somewhere, in whether there is or there isn’t a dot

Unlike with the dot matrix picture, we do not see neurons making up our consciousness, so the analogy falls apart. We can’t really say the contents of our mind are made up of neurons, because there are no neurons inside the mind. Sure, neurons play a role in the generation of the mind’s contents, but the relation is not one of supervenience, at least, not physical supervenience. And there is mind itself too. Mind is no pattern: the thing that maybe supervenes on neurons is the movie, but mind is the screen the movie plays on. The screen we cannot observe.

There is also something more subtle going on in positing that in a dot-matrix picture there is nothing but dots and non-dots. What about the picture itself? Is it pareidolia? While trying to argue against mereological nihilism would take us too far afield, it is something to consider.

Dualism

Now, this is where it gets fun, because in rejecting physicalism the reflex is to reach for dualism, the view that there is the mental and the physical, but this view also makes no sense. It is also the most commonsense view on consciousness, as all talk of mind and brain as two distinct things is inherently dualistic, and it seems impossible to escape such language when talking of consciousness. There are two main varieties. The first one:

Interactionism

Descartes explained this dualism best: there are two substances, mind and matter. Matter operates according to mechanical laws, is extended in space, and has no qualities. Mind isn’t, and its essential property is that it thinks. The qualities of matter (heat, color, etc.) are not in matter: they are in the mind. Mind interacts with matter, interfering with the cause and effect of the brain. Basically, it’s a ghost pulling levers. Where are these levers? Descartes posited the pineal gland, the so-called seat of the soul. The control room where the little homunculus that is you lives. Of course, there is no control room inside the pineal gland. There is no control room anywhere in the brain. And we don’t observe any causality violation in there either. So how does this immaterial ghost in the machine do anything? How can something not physical interact with the physical? If it interacts, why is everything about the brain strict cause and effect1?

While common sense is the way in many contexts, clearly, this is not one of them.

Being less common-sensical, some schools of thought argue that God is constantly creating the universe, making what we call cause and effect an act of will. Similarly, perhaps one could argue that what appears to be the causal operation of the brain is actually willed, but Occam’s razor clearly discards that.

These problems may make one reach for:

Epiphenomenalism

Epiphenomenalism is the assertion that the brain produces the mind and that the mind has no influence on the brain. Thomas Huxley aptly summarized it when he compared the mind to a steam whistle that contributes nothing to the work of a locomotive. The problem with this view is that if mind is fundamentally equivalent to car exhaust, why on earth is it so coherent and stable to be a mind? In this view, since mind is not forced to do anything, as there is no selection pressure on mind, why, then mind could be anything at all. Perhaps the epiphenomenalists would like to gesture at the structure of the brain to explain this coherence (though the brain is famously incoherent), but even if the brain were a far more orderly place, why would this order result in an orderly mind? Car exhaust is the result of very rigid machines and is utterly chaotic in ways minds simply aren’t. Again, one can’t say the mind’s structure is an imprint of the brain’s structure, because the brain is an inscrutable mess! If the brain lent its own structure to the mind, we should expect having a mind to be very confusing indeed, more confusing than even the typical dream.

Perhaps one could argue that what we see in the brain is the encoded data of the mind, but then, where does it get decoded? Where does the simplification occur? Because the brain is not simple.

There is also the following big, big issue: since mind does not interact with the brain, how could the brain know anything about the mind? Because we certainly know about the contents of our own minds, and since under epiphenomenalism, this knowledge is all coming from the brain…

There is also the argument as to why the brain would be wasting that much energy in generating something it has no use for. Bodies are fairly well optimized: surely this would have been optimized away fairly quickly.

Though there is a certain morbid charm in conceptualizing oneself as basically a fart, this concept doesn’t make much sense.

Idealism

I said eliminativism is the most extravagant notion philosophy ever produced, but it is closely followed by its diametric opposite, idealism, the view that all is mind. The earlier mentioned George Berkeley was the chief proponent of this view, though it also crops up in Eastern religions, many of which hold to the view reality is basically a dream. Berkeley was actually a pretty canny guy: what he argued was that there is no quality-less substance such as the laws of physics describe. The qualities we perceive through the senses, the varied, colorful world, is actually all there is. Something that is unperceived does not exist: to the perennial question ‘If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?’ the idealist cheerfully answers ‘No! Also, there is no tree either’.

To clarify why someone would think that, Berkeley brought up the example of a hot rock. Where is this heat? Heat being a qualia (though Berkeley did not use that word), the heat is clearly in the mind. And it’s the same with all the qualities of the rock: they are all in the mind. Something unperceived has no qualities, and therefore no being. It’s not real until it’s observed. Therefore, all is mind.

Now that I write that out, there is a disturbing resemblance between that view and the quantum mechanical fact that elementary particles don’t have definite properties until measurement occurs. Could this somehow be the redemption of idealism?

Think again. Another rejection of idealism I can recall, other than the kicking of a rock, is an apocryphal story of Berkeley getting a door slammed in his face. Let him walk through the door, if all is mind. Because mind and its contents are, after all, a very protean, malleable thing, not at all like a door.

I’m also pretty sure that if a meteorite landed on me and I were completely alone, it would kill me in spite of being unperceived. Berkeley would explain that the meteorite was actually perceived by the mind of God, which I am sure would be of great comfort as I disintegrate under the light of fate.

What now?

David Chapman is right: we can’t say coherent things about consciousness. This is liberating. It’s what makes consciousness the skeleton key, the skeleton key that opens any cage for your head you might be wearing. It cannot be pinned down, making you the unseen thing, the holy of holies. Which is a very grand thing.

As it is, I do have a view of consciousness that I haven’t encountered within philosophy. Which is: the eliminativists are right, mind has no being. What consciousness reveals is that there is something it is like to be nothing.

What could that mean? If anything, maybe there is good reason to believe death is not the end. How can nothing be destroyed?

Alas, this makes no sense either. But!

So.

What bullshit are you believing in?

Actually, there are random, unpredictable effects in the brain. It’s certainly interesting to ponder whether the randomness is not evidence for the intervention of a will, but that seems highly speculative.

I don't think it's entirely correct to say a meteorite hitting you is unperceived.

What if perception isn't exclusive to humans or animals? What if everything has qualia to some degree and "objective" reality is just the sun total of all intersubjectivity? If a tree falls and no human is around then no human perceives it, but the tree might be said to perceive it in some way. This seems to me to fit with quantum mechanics in that the "observer" talked about in wave form collapse is not actually referring to a conscious human observer, but instead can refer to an instrument taking a measure. All interaction of all thing is some level of measure. A rock takes the measure of the rain when it erodes. It's qualia is certainly not the same as ours but who is to say there is no qualia? We can't even prove the qualia of other humans, we merely infer it from our own similar experiences.

Great work! The essay's basically a much more rigorous, scientifically argued version of a post idea I've been toying with for a while now, which would basically argue that supernaturalism and naturalism are in a perpetual stalemate.

Naturalism can say 'I've got Occam's razor on my side; consciousness need be nothing but physically emergent; ideas of a "mind" or a coherent "self" are just stories the self-aware brain tells itself. "Minds" change radically, or even switch off altogether, as a result of sleeping, being half-awake, taking substances, being concussed, being under anesthesia, having dementia, etc. You can even switch the "self" part of the brain off via physical means. Change the brain and you change the person; it's all just brain-states.'

And supernaturalism can reply 'There's tons of anecdotal evidence about out-of-body experiences where the subject knows things they shouldn't be able to know, plus interesting scientific work on reincarnation, etc. More fundamentally, as soon as you claim something is "true" or "false" you're appealing to a world beyond matter. It's not possible for a physical fact (the brain) to make a truth claim about another physical fact (the universe): why give this godlike status to rationality if it's just a brain state among other brain states? Yes, reason's a useful shared standard for seeking agreement among other reasoners, but that's not the same as saying it's actually telling you anything about the world. Even saying "we evolved to understand our environment" involves making any number of philosophical assumptions about time, space, causality, information and the ontological status of matter.'

Me? I choose supernaturalism, because it feels better and, depending on the mood I'm in, truer :)